Episcopal Church (United States)

The arms of the Episcopal Church includes both the cross of St. George and a St. Andrew's cross. |

|

| Primate | Katharine Jefferts Schori |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | 815 Second Avenue New York, NY, USA |

| Territory | The United States and dioceses in Taiwan, Central and South America, the Caribbean, and Europe |

| Members | 2,057,292 baptized[1] |

| Website | EpiscopalChurch.org |

| Anglicanism Portal | |

The Episcopal Church is the Province of the Anglican Communion in the United States, Honduras, Taiwan, Colombia, Ecuador, Haiti, the Dominican Republic, Venezuela, the British Virgin Islands and parts of Europe.[2][3][4] As of 2010, it is a church of 2,057,292 baptized members making it the fifteenth largest Christian denomination in the U.S.[1][5] In keeping with Anglican tradition and theology, the Episcopal Church considers itself "Protestant, yet Catholic".[6]

The Church was organized shortly after the American Revolution when it was forced to separate from the Church of England, as Church of England clergy were required to swear allegiance to the British monarch.[7] It became, in the words of the 1990 report of the Archbishop of Canterbury's Group on the Episcopate, "the first Anglican Province outside the British Isles".[8] Today it is divided into nine provinces and has dioceses outside the U.S. in Taiwan, Central and South America, the Caribbean and Europe. The Episcopal Diocese of the Virgin Islands encompasses both American and British territory.

The Episcopal Church was active in the Social Gospel movement of the late nineteenth century. Since the 1960s and 1970s, it has opposed the death penalty and supported the civil rights movement and affirmative action. Some of its leaders and priests marched with civil rights demonstrators. Today the Church calls for the full civil equality of gay men and lesbians. Most dioceses ordain openly gay men and women; in some, same-sex unions are celebrated with services of blessing. In 2009, the Church's General Convention passed resolutions that allowed for gay and lesbian marriages in states where it is legal.[9] On the question of abortion, the Church has adopted a nuanced position. About all these issues, individual members and clergy can and do frequently disagree with the stated position of the Church.

The Episcopal Church ordains women to the priesthood as well as the diaconate and the episcopate. The current Presiding Bishop of the Episcopal Church is Katharine Jefferts Schori, the first female primate in the Anglican Communion.

Contents

|

Official names

There are two official names of the Episcopal Church specified in its constitution: The Episcopal Church and Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America. The Episcopal Church is the most commonly used name.[2][3][4]

Early in the Church's history, Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America was used. In the middle of the 19th century, some began trying to drop the word Protestant from the church's name, on the grounds that the original break of the Church of England from the Roman Catholic Church had nothing directly to do with the Protestant Reformation. Also, it had often come to mean anti-Catholic rather than non-papal. In a 1964 General Convention compromise, priests and lay delegates suggested adding a preamble to the Church's constitution, recognizing The Episcopal Church as a lawful alternate designation while still retaining the earlier name.

The fight continued until the 66th General Convention voted in 1979 to use the name Episcopal Church (dropping the adjective "Protestant") in the Oath of Conformity of the Declaration for Ordination.[10] The 68th General Convention in 1985 rejected a resolution that would have changed the constitution to delete the older name.[11]

The preamble to the Constitution of the Episcopal Church now reads:

The Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America, otherwise known as The Episcopal Church (which name is hereby recognized as also designating the Church), is a constituent member of the Anglican Communion, a Fellowship within the One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic Church, of those duly constituted Dioceses, Provinces, and regional Churches in communion with the See of Canterbury, upholding and propagating the historic Faith and Order as set forth in the Book of Common Prayer.[12]

The evolution of the name can be seen in the Episcopal Church's Book of Common Prayer (BCP). In the 1928 BCP, the title page said, "According to the use of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America". In contrast, the change in self-identity can be seen in the title page of the 1979 Book of Common Prayer, which states, "'According to the use of The Episcopal Church".[13]

The Episcopal Church communicates in English, Spanish and French because it has dioceses in Asia, Central and South America, and Europe.[14][15] In Spanish the church is called La Iglesia Episcopal Protestante de los Estados Unidos de América or La Iglesia Episcopal and in French L'Église protestante épiscopale dans les États unis d'Amérique or L'Église épiscopale.[16][17]

The alternate name Episcopal Church in the United States of America is commonly seen but has never been the official name of the Episcopal Church. Because it contains integral jurisdictions in many other countries, it was thought that a name was needed which is not directly tied to the United States. But since several other churches in the Anglican Communion also use the name "Episcopal", the phrase in the United States of America is often added, for example by the Anglican Communion's official website[18] and by Anglicans Online.[19]

The full legal name of the national church corporate body is the Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America,[12] which was incorporated by the legislature of New York and established in 1821. The membership of the corporation "shall be considered as comprehending all persons who are members of the Church".[12][20]

History

Church of England in the American colonies (1604–1775)

The Episcopal Church has its origins in the Church of England in the American colonies, and it stresses its continuity with the early universal Western church and maintains apostolic succession.[21] The first parish was founded in Jamestown, Virginia, in 1607 under the charter of the Virginia Company of London.[22]

Although there was no American bishop in the colonial era, the Church of England had an official status in several colonies, which meant that tax money was paid to the local parish by the local government, and the parish handled some civic functions. The Church of England was designated the established church in Virginia in 1609, New York in 1693, in Maryland in 1702, in South Carolina in 1706, in North Carolina in 1730, and in Georgia in 1758. The vestry used the tax money to build and operate churches and to handle poor relief. Virginia attempted to make requirements about attendance, but with a severe shortage of clergy, they were not enforced.

From 1635, the vestries and the clergy were loosely under the diocesan authority of the Bishop of London. In 1660, the clergy of Virginia petitioned for a bishop to be appointed to the colony. This proposal was vigorously opposed by powerful vestrymen, the wealthy planters, who foresaw their interests being curtailed. Subsequent proposals from successive bishops of London for the appointment of a resident suffragan bishop, or another form of office with delegated authority to perform episcopal functions, met with intense local opposition.

During the English Civil War, the episcopate was under attack in England. The Archbishop of Canterbury, William Laud, was beheaded in 1645. Thus, the formation of a North American diocesan structure was hampered and hindered.

In 1649, England founded a missionary organization called the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in New England or the New England Society, for short.[23]

After 1702, the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts (SPG) began missionary activity throughout the colonies. The ministers were few, the glebes small, the salaries inadequate, and the people quite uninterested in religion, as the vestry became in effect a kind of local government.[22] One historian has explained the workings of the parish:

The parish was a local unit concerned with such matters as the conduct and support of the parish church, the supervision of morals, and the care of the poor. Its officers, who made up the vestry, were ordinarily influential and wealthy property holders chosen by a majority of the parishioners. They appointed the parish ministers, made local assessments, and investigated cases of moral offense for referral to the county court, the next higher judicatory. They also selected the church wardens, who audited the parish accounts and prosecuted morals cases. For several decades the system worked in a democratic fashion, but by the 1660s, the vestries had generally become self-perpetuating units made up of well-to-do landowners. This condition was sharply resented by the small farmers and servants.—Clifton Olmstead, History of Religion in the United States[24]

On the eve of Revolution about 400 independent congregations were reported throughout the colonies.

American Revolution (1775–1783)

Embracing the symbols of the British presence in the American colonies, such as the monarchy, the episcopate, and even the language of the Book of Common Prayer, the Church of England almost drove itself to extinction during the upheaval of the American Revolution.[25] More than any other denomination, the War of Independence internally divided both clergy and laity of the Church of England in America, and opinions covered a wide spectrum of political views: patriots, conciliators, and loyalists. On one hand, Patriots saw the Church of England as synonymous with "Tory" and "redcoat". On the other hand, about three-quarters of the signers of the Declaration of Independence were nominally Anglican laymen, including Thomas Jefferson, William Paca, and George Wythe.[7][7] A large fraction of prominent merchants and royal appointees were Anglicans and loyalists. About 27 percent of Anglican priests nationwide supported independence, especially in Virginia. Almost 40 percent (approaching 90 percent in New York and New England) were Loyalists. Out of 55 Anglican clergy in New York and New England, only three were Patriots, two of those being from Massachusetts. In Maryland, of the 54 clergy in 1775, only 16 remained to take oaths of allegiance to the new government.[26]

William Smith made the connection explicit in a 1762 report to the Bishop of London. "The Church is the firmest Basis of Monarchy and the English Constitution", he declared. But if dissenters of "more Republican ... Principles [with] little affinity to the established Religion and manners" of England ever gained the upper hand, the colonists might begin to think of "Independency and separate Government". Thus "in a Political as well as religious view", Smith stated emphatically, the church should be strengthened by an American bishop and the appointment of "prudent Governors who are friends of our Establishment".[27] Amongst the clergy, more or less, the northern clergy were loyalist and the southern clergy were patriot.[7] Partly, their pocketbook can explain clergy sympathies, as the New England colonies did not establish the Church of England and clergy depended on their SPG stipend rather than their parishioners' gifts. When war broke out, these clergy looked to England for both their paycheck and their direction. Where the Church of England was established, mainly the southern colonies, financial support was local and loyalties were local.[7]

Of the approximately three hundred clergy in the Church of England in America between 1776 and 1783, over 80 percent in New England, New York, and New Jersey were loyalists. This is in contrast to the less than 23 percent loyalist clergy in the four southern colonies.[7] In two colonies, only one priest was a patriot - Samuel Provoost, who would become bishop, in New York and Robert Blackwell, who would serve as a chaplain in the Continental Army, in New Jersey. Many Church of England clergyman remained loyalists as they took their two ordination oaths very seriously. The first oath arises from the Church of England canons of 1604 where Anglican clergy must affirm that the king,

within his realms of England Scotland, and Ireland, and all other his dominions and countries, is the highest power under God; to whom all men ...do by God's laws owe most loyalty and obedience, afore and above all other powers and potentates in earth".[7]

Thus, each Anglican clergyman was obliged to swear publicly allegiance to the king. The second oath arose out of the Act of Uniformity of 1662 where clergy were bound to use the official liturgy as found in the Book of Common Prayer and to read it verbatim. This included prayers for the king and the royal family and for the British Parliament.[7] These two oaths and problems worried the consciences of clergymen. Some clergy were clever in their avoidance of these problems.[7] Samuel Tingley, a priest in Delaware and Maryland, rather than praying "O Lord, save the King" opted for evasion and said "O Lord, save those whom thou hast made it our especial Duty to pray for".[7]

In general, loyalist clergy stayed by their oaths and prayed for the king or else suspended services.[7] By the end of 1776, Anglican churches were closing.[7] An SPG missionary would report that of the colonies of Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, and Connecticut which he had intelligence of, only the Anglican churches in Philadelphia, a couple in rural Pennsylvania, those in British-controlled New York, and two parishes in Connecticut were open.[7] Anglican priests held services in private homes or lay readers who were not bound by the oaths held morning and evening prayer.[7]

Nevertheless, some Loyalists clergymen were defiant. In Connecticut, John Beach conducted worship throughout the war and swore that he would continue praying for the king.[7] In Maryland, Jonathan Boucher took two pistols into the pulpit and even pointed a pistol at the head of a group of patriots while he preached on loyalism.[7] Charles Inglis, rector of Trinity Church in New York, persisted in reading the royal prayers even when George Washington was seated in his congregation and a patriot militia company stood by observing the service.[7][23] The consequences of such bravado were very serious.[7] During 1775 and 1776, the Continental Congress had issued decrees ordering churches to fast and pray on behalf of the patriots.[7] Starting July 4, 1776, Congress and several states passed laws making prayers for the king and British Parliament acts of treason.[7]

The patriot clergy in the South were quick to find reasons to transfer their oaths to the American cause and prayed for the success of the Revolution.[7] One precedent was the transfer of oaths during the Glorious Revolution in England.[7] Most of the patriot clergy in the south were able to keep their churches open and services continued.[7]

Early nation: 1783-1800

In the wake of the Revolution, American Episcopalians faced the task of preserving a hierarchical church structure in a society infused with republican values. By 1786, the church had succeeded in translating episcopacy to America and in revising the Book of Common Prayer to reflect American political sensibilities. Later, through the efforts of Bishop Philander Chase (1775–1852) of Ohio, Americans successfully sought material assistance from England for the purpose of training Episcopal clergy. The development of the Protestant Episcopal Church provides an example of how Americans in the early republic maintained important cultural ties with England.[28]

When peace returned in 1783, about 80,000 Loyalists (about 15 percent of the total) went into exile. Most – about 50,000 – heading for Canada including Charles Inglis, who would become the first colonial bishop.[7][23] By 1790, in a nation of four million, Anglicans were reduced to about ten thousand.[7] In Virginia, less than 42 parishes of the 107 that existed in 1784 were able to support a priest between 1802 and 1811.[7] In Georgia, Christ Church, Savannah was the only active parish in 1790.[7] In Maryland, half of the parishes remained vacant by 1800.[7] For a period after 1816, North Carolina had no clergy when its last clergyman died.[7] Bishop Samuel Provoost of New York, one of the first three Episcopal bishops, was so disheartened that he resigned his position in 1801 and retired to the country to study botany having given up on the Episcopal Church, which he was convinced would die out with the old colonial families.[7]

The church was disestablished in all the states during the American Revolution. Buckley (1988) examines the debates in the Virginia legislature and local governments that culminated in the repeal of laws granting government property to the Episcopal Church. The Baptists took the lead in disestablishment, with support from Thomas Jefferson and, especially, James Madison. Virginia was the only state to seize property belonging to the established Episcopal Church. The fight over the sale of the glebes, or church lands, demonstrated the strength of certain Protestant groups in the political arena when united for a course of action.[29]

Bishops

Prior to the war, the introduction of a bishop from Britain into the colonies was opposed in the north by Puritan descendants suspicious of episcopal prerogatives and in the south by Anglicans accustomed to lay initiative. When the clergy of Connecticut elected Samuel Seabury as their bishop in 1783, he sought consecration in England. The Oath of Supremacy prevented Seabury's consecration in England, so he went to Scotland; the non-juring Scottish bishops there consecrated him in Aberdeen on November 14, 1784, making him, in the words of scholar Arthur Carl Piepkorn, "the first Anglican bishop appointed to minister outside the British Isles".[30]

In return, the Scottish bishops requested that the Episcopal Church use the longer Scottish prayer of consecration during the Eucharist, instead of the English prayer. Seabury promised that he would endeavor to make it so. Seabury returned to Connecticut in 1785 and made New London his home, becoming rector of St James Church there. A meeting of his Connecticut clergymen was held during the first week of August 1785 at Christ Church on the South Green in Middletown. At the August 2, 1785, reception of the bishop, his letters of consecration were requested, read, and accepted. On August 3, 1785, the first ordinations on American soil took place there at Christ Church. Four men, Henry Van Dyke, Philo Shelton, Ashbel Baldwin, and Colin Ferguson, were ordained to the Holy Order of Deacons that day. On August 7, 1785, Collin Ferguson was advanced to the priesthood, and Thomas Fitch Oliver was admitted to the diaconate. Seabury said, prophetically, of Christ Church in Middletown, "Long may this birthplace be remembered, and may the number of faithful stewards who follow this succession increase and multiply till time shall be no more". Over the next 100 years there were 274 ordinations in Middletown.

In 1787, two priests – William White of Pennsylvania and Samuel Provoost of New York – were consecrated as bishops by the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Archbishop of York, and the Bishop of Bath and Wells, the legal obstacles having been removed by the passage through Parliament of the Consecration of Bishops Abroad Act 1786. Thus there are two branches of Apostolic succession for the American bishops:

- Through the non-juring bishops of Scotland that consecrated Samuel Seabury.

- Through the English church that consecrated William White and Samuel Provoost.

All bishops in the American Church are ordained by at least three bishops. One can trace the succession of each back to Seabury, White and Provoost. (See Succession of Bishops of the Episcopal Church.)

In 1789, representative clergy from nine dioceses met in Philadelphia to ratify the Church's initial constitution. The Episcopal Church was formally separated from the Church of England in 1789 so that clergy would not be required to accept the supremacy of the British monarch. A revised version of the Book of Common Prayer was written for the new church that same year.

The fourth bishop of the Episcopal Church was James Madison, the first bishop of Virginia. Madison was consecrated in 1790 by the Archbishop of Canterbury and two other Church of England bishops. This third American bishop consecrated within the English line of succession occurred because of continuing unease within the Church of England over Seabury's nonjuring Scottish orders.[7]

American bishops such as William White (1748–1836), John Henry Hobart (1775–1830), and Philander Chase provided models of civic involvement, pastoral dedication, and evangelism, respectively.[31]

Nineteenth century

As the United States grew, new dioceses were established, as well as the Convocation of American Churches in Europe.

In 1856 (before the American Civil War) the first society for African Americans in the Episcopal Church was founded by James Theodore Holly. Named The Protestant Episcopal Society for Promoting The Extension of The Church Among Colored People, the society argued that blacks should be allowed to participate in seminaries and diocesan conventions. The group lost its focus when Holly emigrated to Haiti, but other groups followed after the Civil War. The current Union of Black Episcopalians traces its history to the society.[32]

Holly went on to found the Anglican Church in Haiti, where he became the first African-American bishop on November 8, 1874. As Bishop of Haiti, Holly was the first African American to attend the Lambeth Conference.[33] However, he was consecrated by the American Church Missionary Society, an Evangelical Episcopal branch of the Church.

Civil War era

When the Civil War began in 1861, Episcopalians in the South formed their own Protestant Episcopal Church. However, in the North the separation was never officially recognized. After the war, Presiding Bishop John Henry Hopkins of Vermont wrote to every Southern bishop to attend the convocation in Philadelphia in October 1865 to pull the church back together again. Only Thomas Atkinson of North Carolina and Henry C. Lay of Arkansas attended from the South. Atkinson, whose opinions represented his own diocese better than it did his fellow Southern bishops, did much nonetheless to represent the South while at the same time paving the way for reunion. A General Council of the Southern Church meeting in Atlanta in November permitted dioceses to withdraw from the church. All withdrew by 16 May 1866, rejoining the national church.[34]

By the middle of the 19th century, evangelical Episcopalians disturbed by High Church Tractarianism formed their own voluntary societies and continued to work in interdenominational agencies. In 1874, a faction established the Reformed Episcopal Church, while those who remained in the older body became known as Broad Church liberals.[35]

Samuel David Ferguson was the first black bishop consecrated by the Episcopal Church, the first to practice in the U.S. and the first black person to sit in the House of Bishops. Bishop Ferguson was consecrated on June 24, 1885, with the then-Presiding Bishop of the Episcopal Church acting as a consecrator.

From the Gilded Age to the 1976 General Convention (1890–1975)

Highly prominent laity such as banker J. P. Morgan, industrialist Henry Ford, and art collector Isabella Stewart Gardner played a central role in shaping a distinctive upper class Episcopalian ethos, especially with regard to preserving the arts and history. Moreover, despite the relationship between an Anglo-Catholicism and Episcopalian involvement in the arts, most of these laypeople were not inordinately influenced by religious thought. These philanthropists propelled the Episcopal Church into a quasi-national position of importance while at the same time giving the church a central role in the cultural transformation of the country.[36] Another mark of influence is the fact that more than a quarter of all presidents of the United States have been Episcopalians (see List of United States Presidential religious affiliations).

It was during this period that the Book of Common Prayer was revised, first in 1892 and later in 1928. In 1940, the Episcopal Shield was adopted. The shield is based on the St George's Cross, a symbol of England (mother of world Anglicanism), with a saltire reminiscent of the Cross of St Andrew in the canton, in reference to the historical origins of the American episcopate in the Scottish Episcopal Church.[37]

The first women were admitted as delegates to General Convention in 1970.[38] In 1975, Vaughan Booker was made a deacon in Graterford State Prison's chapel in Pennsylvania, becoming the first convicted murderer to be ordained in the Episcopal Church.[39]

Modernization and controversy (1976 to the present)

The modernization of the church has included both controversial and non-controversial moves related to racism, theology, worship, homosexuality, the ordination of women, the institution of marriage, and the adoption of a new prayerbook, which can be dated to the General Convention of 1976. The most contentious issues have been the ordination of women, the role of homosexuals in the church, the institution of marriage, and the liberalization of traditional theological concepts (see "Responses to the controversies" below)..[40]

Regarding racism the 1976 General Convention passed a resolution calling for an end to apartheid in South Africa and in 1985 called for "dioceses, institutions, and agencies" to create equal opportunity employment and affirmative action policies to address any potential "racial inequities" in clergy placement. In 1991 the General Convention declared "the practice of racism is sin"[41] and in 2006 a unanimous House of Bishops endorsed Resolution A123 apologizing for complicity in the institution of slavery and silence over "Jim Crow" laws, segregation, and racial discrimination.[42]

The 1976 General Convention also approved the ordination of women and a new prayerbook, which was a substantial revision and modernization of the previous 1928 edition. It incorporated many principles of the Roman Catholic Church's liturgical movement, which had been discussed at Vatican II. This version was adopted as the official prayerbook in 1979 after an initial three-year trial use. Several conservative parishes, however, continued to use the 1928 version.

Women's ordination

Following upon years of discussion in the Episcopal Church and elsewhere, in 1976, the General Convention amended Canon law to permit the ordination of women to the priesthood. While most dioceses of the Episcopal Church ordain women as priests and bishops, the full Anglican Communion does not universally accept the ordination of women. At the present time, three U.S. dioceses do not ordain women at all. Many other churches in the Anglican Communion, including the Church of England, ordain women as deacons or priests, but only a few have women serving as bishops. Objections to the ordination of women have been different from time to time and place to place. Some believe that it is fundamentally impossible for a woman to be validly ordained, while others believe it is possible but inappropriate. Considerations cited include local social conditions, ecumenical implications, or the symbolic character of the priesthood and a belief that only a male person could adequately symbolize Christ.

The first women were canonically ordained to the priesthood in 1977. (Previously, the "Philadelphia Eleven" were uncanonically ordained on July 29, 1974, in Philadelphia.[43] Other "irregular" ordinations also occurred in 1974, notably in Palo Alto. These "irregular" ordinations were also reconciled at the 1976 GC.)[44]

The first female bishop, Barbara Harris, was consecrated on February 11, 1989.[45] The General Convention reaffirmed in 1994 that both men and women may enter into the ordination process, but also recognized that there is value to the theological position of those who oppose women's ordination. It was not until 1997 that the GC declared that "the ordination, licensing and deployment of women are mandatory" and that dioceses that have not ordained women by 1997 "shall give status reports on their implementation".[46] This has not ended the controversy over women's ordination.

2006 election of Katherine Jefferts Schori as Presiding Bishop

The 2006 election of Jefferts Schori as the Church's 26th presiding bishop was controversial in the wider Anglican Communion because she is a woman and the full Anglican communion does not recognize the ordination of women. She is the only national leader of a church in the Anglican Communion who is a woman. Prior to her election she was Bishop of Nevada. She was elected at the 75th General Convention on June 18, 2006, and invested at the Washington National Cathedral on November 4, 2006.

Jefferts Schori generated controversy when she voted to confirm openly gay Gene Robinson as a bishop and for allowing blessings of same-sex unions in her diocese of Nevada.

Ten primates of the Anglican communion have stated that they do not recognize Presiding Bishop Jefferts Schori as a primate. In addition, eight American dioceses have rejected her authority and have asked the Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams to assign them another national leader.[47]

Homosexuality

The Episcopal Church affirmed at the 1976 General Convention that homosexuals are "children of God" who deserve acceptance and pastoral care from the church. It also called for homosexual persons to have equal protection under the law. This was reaffirmed in 1982.

Despite these affirmations of gay rights, the General Convention affirmed in 1991 that "physical sexual expression" is only appropriate within the monogamous, lifelong "union of husband and wife."[48] In 2009, the General Convention charged the Standing Commission on Liturgy and Music to develop theological and liturgical resources for same-sex blessings and report back to the General Convention in 2012. It also gave bishops an option to provide "generous pastoral support" especially where civil authorities have legalized same-gender marriage, civil unions, or domestic partnerships.[49]

In 1994, the GC determined that church membership would not be determined on "marital status, sex, or sexual orientation". The GC also discourages the use of conversion therapy to "change" homosexuals into heterosexuals.[50]

On July 14, 2009, the Episcopal Church's House of Bishops voted that "any ordained ministry" is open to gay men and lesbians.[51] The New York Times said the move was "likely to send shockwaves through the Anglican Communion."[52] This vote ended a moratorium on ordaining gay bishops passed in 2006 and passed in spite of Archbishop Rowan Williams's personal call at the start of the convention that, "I hope and pray that there won't be decisions in the coming days that will push us further apart."[51] N. T. Wright, a leading New Testament and Anglican scholar as well as Bishop of Durham in the Church of England, wrote in The Times (London) that the vote "marks a clear break with the rest of the Anglican Communion" and formalizes the Anglican schism.[53] However, in another resolution the Convention voted to "reaffirm the continued participation" and "reaffirm the abiding commitment" of the Episcopal Church with Anglican Communion.[54]

The first openly gay priest, Robert Williams, was ordained by Bishop John Shelby Spong in 1989.[55] The ordination provoked a furor. The next year Barry Stopfel was ordained a deacon by Bishop Spong's assistant, Walter Righter. Because Stopfel was not celibate, this resulted in a trial under canon law. The church court dismissed the charges on May 15, 1996, stating that "no clear doctrine"[56] prohibits ordaining a gay or lesbian person in a committed relationship.[57]

The first openly homosexual bishop, Gene Robinson, was elected on June 7, 2003, at St. Paul's Church in Concord, New Hampshire. Thirty-nine clergy votes and 83 lay votes was the threshold necessary to elect a bishop in the Episcopal Diocese of New Hampshire at that time. The clergy voted 58 votes for Robinson and the laity voted 96 for Robinson on the second ballot. Consent to the election of Robinson was given at the 2003 General Convention. The House of Bishops voted in the affirmative, with 62 in favor, 43 opposed, and 2 abstaining. The House of Deputies, which consists of laypersons and priests, also voted in the affirmative: the laity voted 63 in favor, 32 opposed, and 13 divided; the clergy voted 65 in favor, 31 opposed, and 12 divided. Robinson was consecrated on November 2, 2003, in the presence of Presiding Bishop Frank Griswold and 47 bishops.[58] Since the ratification of Robinson as bishop, some clergy and lay members have left the Episcopal Church (see Anglican realignment). In October 2003, an emergency meeting of the Anglican primates (the heads of the Anglican Communion's 38 member churches) was convened. The meeting's final communiqué included the warning that if Robinson's consecration proceeded, it would "tear the fabric of the communion at its deepest level."[59]

According to the Windsor Report of the Anglican Communion, the 2003 consecration of Robinson, divorced father of two and an openly gay man living in a committed relationship, was a landmark event for those on both sides of the issue.

On one side of the debate, the 1998 Lambeth Conference 1.10 is quoted, which states:

"This Conference ... in view of the teaching of Scripture, upholds faithfulness in marriage between a man and a woman in lifelong union, and believes that abstinence is right for those who are not called to marriage."[60]

In answer, at the request of the Anglican Communion's Lambeth Commission, the Episcopal Church released To Set Our Hope on Christ on June 21, 2005, which explains "how a person living in a same gender union may be considered eligible to lead the flock of Christ."[61]

Responses to the controversies

Dissenters have dealt with these controversial moves in various ways, the most notable, perhaps, being the Anglican Church in North America, which officially organized in 2009, forming an ecclesiastical structure apart from the Episcopal Church.[62][62][63] Former Episcopal Church leader Bishop Robert Duncan was elected as primate and the ACNA, which was reported to have approximately 100,000 members and over 700 parishes at the time of its formation in 2009.[52][62][63] The ACNA has not been received as an official member of the Anglican Communion by the Church of England, but many Anglican churches of the global south, such as Nigeria and Uganda which represent approximately 1/3 of the worldwide Anglican Communion, have declared themselves to be in full communion with it.

The two main movements in response to the controversies within the Episcopal Church are generally referred to as the Continuing Anglican movement and Anglican realignment.

Secession and realignment

In 1977, 1,600 bishops, clergy and lay people met in St. Louis and formed the Congress of St. Louis under the leadership of retired Episcopal Bishop Albert Chambers.[64] This began the Continuing Anglican Movement with the passage of the Affirmation of St. Louis. Many other conservative groups have continued to break away out of frustration over the Church's position on homosexuality, the ordination of openly homosexual priests and bishops, and abortion among others.

At this point three full diocesan conventions have voted to withdraw from the Episcopal Church: the Diocese of San Joaquin, the Diocese of Fort Worth and the Diocese of Pittsburgh. This does not include individual congregations that have also withdrawn, like in the Diocese of Virginia when members of eight parishes voted to leave the Episcopal Church, including the historic Falls Church and Truro Church. These congregations then formed the Anglican District of Virginia, which became part of the Convocation of Anglicans in North America (CANA).

The first diocesan convention to vote to break with the Episcopal Church (which has 110 dioceses) was the Episcopal Diocese of San Joaquin.[65] On December 8, 2007, the convention of the Episcopal Diocese of San Joaquin voted to secede from the Episcopal Church and join the Anglican Province of the Southern Cone, a more conservative and traditional member of the Anglican Communion located in South America.[66] The diocese had 48 parishes.[67] On July 21, 2009, the Superior Court of California ruled that the diocese cannot leave the Episcopal Church and that these acts were void.[68] On October 4, 2008, the convention of the Episcopal Diocese of Pittsburgh also voted to leave the Episcopal Church and join the Province of the Southern Cone. This split occurred after Presiding Bishop Jefferts Schori called an emergency meeting of the House of Bishops, which deposed Bishop Robert Duncan from office in September 2008. Bishop Duncan had led the diocese for 11 years.[69]

The conventions of the Diocese of Quincy in Illinois and the Diocese of Fort Worth voted in November 2008 to leave the Episcopal Church.[69] On November 15, 2008, the convention of the Diocese of Fort Worth, under the leadership of Bishop Jack Leo Iker and with the vote of 80 percent of the voting clergy and laity, also voted to align with the Province of the Southern Cone.[70] In response to the departure of Iker and the Fort Worth diocese, Presiding Bishop Schori declared that Iker had "abandoned the communion" and instituted a law suit against Iker and followers, seeking to oust Iker and his followers from church buildings and property.[71] On November 16, 2009, the appellate court issued an order staying the litigation while certain procedural issues were decided by the appellate court.[72] On April 27, 2010, the Second Court of Appeals in Fort Worth heard oral argument on issues that may determine whether the litigation will be allowed to proceed at the trial level.[73]

Jefferts Schori has criticized these moves and stated that schism is not an "honored tradition within Anglicanism" and claims schism has "frequently been seen as a more egregious error than charges of heresy." [69] In each diocese where parishioners have voted to leave, the Episcopal Church is reforming diocesan and parish structure.

Church property controversies

In 1993, the Connecticut Supreme Court concluded that former parishioners of a local Episcopal church could not keep the property held in the name of that parish because it found that a relationship existed between the local and general church such that a legally enforceable trust existed in favor of the general church over the local church's property.[74]

On December 19, 2008, a Virginia trial court ruled that eleven congregations of former Episcopalians could keep parish property when the members of these congregations split from the Episcopal church to form the Anglican District of Virginia (ADV).[75] The Episcopal Church claimed that the property belonged to it under the canon law of the Episcopal Church and has appealed the decision.[76]

Recent rulings in Colorado and California have ordered congregations that have voted to change their associations within the Anglican Communion to return their properties to the Episcopal Church.[77] On January 5, 2009, the California Supreme Court ruled that St. James Anglican Church in Newport Beach could not keep property held in the name of an Episcopal parish. The court concluded that even though the local church's names were on the property deeds for many years, the local churches had agreed to be part of the general church.[78]

Membership

Total membership of active baptized members in 2009 within the United States is 2,057,292, according to the 2010 National Council of Churches Report[79], which represents a 2.81% decline from the NCC's figure for 2008. The statistics for the most recent year available from the Episcopal Church itself, 2007, are 2,116,749 in the United States and 2,285,143 worldwide, which are calculated from all submitted parochial reports for 2007 – the latest year available[update].[80]

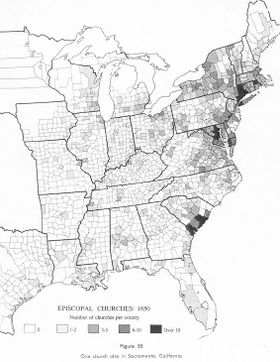

In recent years many mainline denominations have experienced a decline in membership.[81] Once changes in how membership is counted are taken into consideration, the Episcopal Church's membership numbers were broadly flat throughout the 1990s, with a slight growth in the first years of the 21st century.[80][82][83][84][85] A loss of 115,000 members was reported for the years 2003–5, which has been attributed in part to controversy concerning ordination of homosexuals to the priesthood and the election of Gene Robinson (who is openly gay) as Bishop of New Hampshire.[86] The Episcopal Church experienced notable growth in the first half of the twentieth century. Membership grew from 1.1 million members in 1925 to a peak of over 3.4 million members in the mid-1960s.[87] Between 1970 and 1990, membership declined from about 3.2 million to about 2.4 million.[87] Membership is concentrated along the east coast. The District of Columbia, Rhode Island, Connecticut, and Virginia have the highest rates of adherence. The state of New York has the largest number of members, with over 200,000.[88]

Structure

The governance the Episcopal Church is Episcopal polity, which is the same as other Anglican churches. Following the American Revolution, American Anglicans were technically not a part of the Church of England's structure, so they had to form their own. The Church has its own system of canon law.

The Episcopal Church is composed of 110 dioceses in the United States, Colombia, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Haiti, Honduras, Puerto Rico, Taiwan, Venezuela and the Virgin Islands. It also includes the Convocation of American Churches in Europe and the Navajoland Area Mission, which are jurisdictions similar to a diocese. The Presiding Bishop is one of three Anglican primates who together exercise metropolitan jurisdiction over the Episcopal Church of Cuba, which is an extraprovincial diocese in the Anglican Communion.[89]

These dioceses are organized into nine provinces. Each province has a synod and a mission budget, but does not have authority over the dioceses which make it up.

Today, there are over 7,000 congregations, each of which elects a vestry or bishop's committee. Subject to the approval of its diocesan bishop, the vestry of each parish elects a priest, called the rector, who has spiritual jurisdiction in the parish and selects assistant clergy, both deacons and priests. (There is a difference between vestry and clergy elections – clergy are ordained members usually selected from outside the parish, whereas any member in good standing of a parish is eligible to serve on the vestry.) The diocesan bishop, however, appoints the clergy for all missions and may choose to do so for non-self-supporting parishes.

The middle judicatory consists of a diocese headed by a bishop. Diocesan conventions are usually held annually. Unlike the Church of England in which bishops are governmental appointees, the bishops in the Episcopal Church are elected at these diocesan conventions, subject to confirmation by the House of Bishops. (All bishops are first ordained priests.)

At the national level, the church is governed by the triennial General Convention, which consists of two bodies:

- The House of Deputies (consisting of 4 laity and 4 clergy from each diocese, usually elected at the diocesan convention).

- The House of Bishops (consisting of all living bishops who have headed dioceses).

The Chief Officer of the Episcopal Church, elected from and by the House of Bishops and confirmed by the House of Deputies at General Convention, is called the Presiding Bishop and serves on term of 9 years.[90]

The location of the Presiding Bishop's office is the Episcopal Church Center, the national administrative headquarters, located at 815 Second Avenue, New York, NY. It is often referred to by Episcopalians simply as "815."[91]

Worship and liturgy

Varying degrees of liturgical practice prevail within the church, and one finds a variety of worship styles: traditional hymns and anthems, more modern religious music, Anglican chant, liturgical dance, charismatic prayer, and vested clergy of varying degrees. As varied as services can be, the central binding aspect is the Book of Common Prayer or supplemental liturgies.

Often a congregation or a particular service will be referred to as Low Church or High Church. In theory:

- High Church, especially the very high Anglo-Catholic movement, is ritually inclined towards embellishments such as incense, formal hymns, and a higher degree of ceremony. In addition to clergy vesting in albs, stoles and chasubles, the lay assistants may also be vested in cassock and surplice. The sung Eucharist tends to be emphasized in High Church congregations, with Anglo-Catholic congregations and celebrants using sung services almost exclusively. Often, due to the effects of the Second Vatican Council on the Roman Catholic Church, some Anglo-Catholic Episcopalian services are actually more elaborate than a modern Roman Catholic Mass.

- Low Church is simpler and may incorporate other elements such as informal praise and worship music. "Low" congregations tend towards a more "traditional Protestant" outlook with its emphasis of Biblical revelation over symbolism. The spoken Eucharist tends to be emphasized in Low Church congregations.

- Broad Church incorporates elements of both low church and high church.

A majority of Episcopalian services could be considered to be "High Church" while still falling somewhat short of a typical Anglo-Catholic "very" high church service. In contrast, "Low Church" services are somewhat rarer. However, while some Episcopalians refer to their churches by these labels, often there is overlapping, and the basic rites do not greatly differ. There are also variations that blend elements of all three and have their own unique features, such as New England Episcopal churches, which have elements drawn from Puritan practices, combining the traditions of "high church" with the simplicity of "low church". Typical parish worship features Bible readings from the Old Testament as well as from both the Epistles and the Gospels of the New Testament.

In the Eucharist or Holy Communion service, the Book of Common Prayer specifies that bread and wine are consecrated for consumption by the people. Those wishing for whatever reason to avoid alcohol are free to decline the cup. A Eucharist can be part of a wedding to celebrate a sacramental marriage and of a funeral as a thank offering (sacrifice) to God and for the comfort of the mourners.

The veneration of saints in the Episcopal Church is a continuation of an ancient tradition from the early Church which honors important people of the Christian faith. The usage of the term "saint" is similar to Catholic and Orthodox traditions. Those inclined to the Anglo-Catholic traditions may explicitly invoke saints as intercessors in prayer.

Book of Common Prayer

The Episcopal Church publishes its own Book of Common Prayer (BCP) (similar to other Anglican BCPs), containing most of the worship services (or "liturgies") used in the Episcopal Church. Because of its widespread use in the church, the BCP is both a reflection of and a source of theology for Episcopalians.

The full name of the BCP is: The Book of Common Prayer and Administration of the Sacraments and Other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church Together with The Psalter or Psalms of David According to the use of The Episcopal Church.

Previous American BCPs were issued in 1789, 1892, and 1928. (A proposed BCP was issued in 1786 but not adopted.) The BCP is in the public domain; however, any new revisions of the BCP are copyrighted until they are approved by the General Convention. After this happens, the BCP is placed into the public domain.

The current edition dates from 1979 and was marked by a linguistic modernization and, in returning to ancient Christian tradition, it restored the Eucharist as the central liturgy of the church. The 1979 version also de-emphasized the notion of personal sin and reflected the theological and worship changes of the ecumenical reforms of the 1960s and 1970s. On the whole, it changed the theological emphasis of the church to be more Catholic in nature. In 1979, the Convention adopted the revision as the "official" BCP and required churches using the old (1928) prayer book to also use the 1979 revision. There was enough strife in implementing and adopting the 1979 BCP that an apology was issued at the 2000 General Convention[92] for any who were "offended or alienated during the time of liturgical transition to the 1979 Book of Common Prayer". The 2000 General Convention also authorized the occasional use of some parts of the 1928 book, under the direction of the bishop.

The 1979 edition contains a provision for the use of "traditional" (Elizabethan) language under various circumstances not directly provided for in the book, and the Anglican Service Book was produced accordingly, as "a traditional language adaptation of the 1979 Book of Common Prayer together with the Psalter or Psalms of David and Additional Devotions."

Doctrine and practice

The center of Episcopal teaching is the life and resurrection of Jesus Christ.[93] The basic teachings of the church, or catechism, include:

- Jesus Christ is fully human and fully God. He died and was resurrected from the dead.

- Jesus provides the way of eternal life for those who believe.

- God the Father, God the Son (Jesus Christ), and God the Holy Spirit, are one God, and are called the Holy Trinity, "Three and yet one"

- The Old and New Testaments of the Bible were written by people "under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit." The Apocrypha are additional books that are used in Christian worship, but not for the formation of doctrine.

- The two great and necessary sacraments are Holy Baptism and Holy Eucharist.

- Other sacramental rites are confirmation, ordination, marriage, reconciliation of a penitent, and unction.

- Belief in heaven, hell, and Jesus' return in glory.

- Emphasis on living out the Greatest Commandment to love God and neighbor fully, as found in the Gospel of Matthew 22:36-40[94]

The full catechism is included in the Book of Common Prayer and posted on Episcopal website here.[95] The threefold sources of authority in Anglicanism are scripture, tradition, and reason. These three sources uphold and critique each other in a dynamic way.

The Episcopal Church follows the via media or "middle way" between Protestant and Roman Catholic doctrine and practices: that is both Catholic and Reformed. Not all Episcopalians self-identify with this image, especially those whose convictions lean toward either evangelicalism or Anglo-Catholicism. There are many different theologies represented within the Episcopal Church. Some Episcopal theologians hold evangelical positions, affirming the authority of scripture over all. The Episcopal Church website glossary defines the sources of authority as a balance between scripture, tradition, and reason. These three are characterized as a "three-legged stool" which will topple if any one overbalances the other. It also notes

- The Anglican balancing of the sources of authority has been criticized as clumsy or "muddy." It has been associated with the Anglican affinity for seeking the mean between extremes and living the via media. It has also been associated with the Anglican willingness to tolerate and comprehend opposing viewpoints instead of imposing tests of orthodoxy or resorting to heresy trials.[96]

This balance of scripture, tradition and reason is traced to the work of Richard Hooker, a sixteenth century apologist. In Hooker's model, scripture is the primary means of arriving at doctrine and things stated plainly in scripture are accepted as true. Issues that are ambiguous are determined by tradition, which is checked by reason.[97] Noting the role of personal experience in Christian life, some Episcopalians have advocated following the example of the Wesleyan Quadrilateral of Methodist theology by thinking in terms of a "Fourth Leg" of "experience." This understanding is highly dependent on the work of Friedrich Schleiermacher.

A public example of this struggle between different Christian positions in the church has been the 2003 consecration of the Right Reverend Gene Robinson, an openly gay man living with a long-term partner. The acceptance/rejection of his consecration is motivated by different views on the authority of and understanding of scripture.[98] This struggle has some members concerned that the church may not continue its relationship with the larger Anglican Church. Others, however, view this pluralism as an asset, allowing a place for both sides to balance each other.

Comedian and Episcopalian Robin Williams once described the Episcopal faith (and, in a performance in London, specifically the Church of England) as "Catholic Lite – same rituals, half the guilt."[99]

Social issues

The preparation materials for delegates to the 2006 General Convention highlighted areas of "Social Teaching/Contentious Resolutions" made by the General Convention in the previous 30 years including race, economic justice, ordination of women, and inclusion. In some areas, such as race, the church has maintained a consistent theme. In other areas, such as human sexuality, the church has faced larger struggles.

On race

- In 1976 the Convention called for an end to apartheid while commending the Anglican Church of Southern Africa (formerly the Church of the Province of Southern Africa) for its ministry.[100]

- In 1979 the Convention condemned the Ku Klux Klan and all similarly racist groups and called on church members to oppose them.[101]

- Between 1982 and 1985 equal opportunity employment and affirmative action were first implemented within the church.[102][103][104][105][106]

- In 1991 the Convention declared that the practice of racism is sin and called on all church members to work to remove racism from the US.[107]

- In 1994 the Convention condemned the "racist and unjust treatment" of immigrants.[108]

On economic justice

- During the Great Depression, places like the Cathedral Shelter of Chicago served the poor.

- In 1991 the Convention recommended parity in pay and benefits between clergy and lay employees in equivalent positions.[109]

- Several times between 1979 and 2003 the Convention expressed concern over affordable housing and supported the church working to provide affordable housing.[110]

- In 1982 and 1997, the Convention reaffirmed the Church's commitment to eradicating poverty and malnutrition and challenged parishes to increase ministries to the poor.[111]

- In 1997 and 2000, the Convention urged the church to promote living wages for all.[112][113]

- In 2003 the Convention urged legislators to raise the US minimum wage and to establish a living wage with health benefits as the national standard.[114][115]

On the ordination of women

- The first women were ordained priests in the Episcopal Church on July 29, 1974, though the orders had not been endorsed by General Convention. The so-called Philadelphia 11 were ordained by Bishops Daniel Corrigan, Robert L. DeWitt, Edward R. Welles, assisted by Antonio Ramos.[116] On September 7, 1975, four more women were irregularly ordained by retired Bishop George W. Barrett.[117] The 1976 General Convention, which approved the ordination of women to the priesthood and episcopate, voted to regularize the 15 forerunners.

- In 1994 the Convention affirmed that there is value in the theological position that women should not be ordained

- In 1997 the Convention affirmed that "the canons regarding the ordination, licensing, and deployment of women are mandatory and that dioceses noncompliant in 1997 shall give status reports on their progress toward full implementation."[46]

- In 2006 the convention elected Katharine Jefferts Schori as Presiding Bishop. She is the first woman to serve as primate in the Anglican Communion.

The three "noncompliant" dioceses were San Joaquin, Quincy, and Fort Worth. The 2006 directory of the North American Association for the Diaconate lists three women deacons in Quincy, 15 in San Joaquin, and 8 in Fort Worth.[118] Fort Worth also allows parishes that wish to call a woman priest to transfer to the jurisdiction of the Diocese of Dallas.

On gender and sexuality

- In 1976 the Convention declared that homosexuals are "children of God" and "entitled to full civil rights".[119]

- In 1979 the Convention endorsed the Equal Rights Amendment and urged legislatures to ratify it.

- In 1988 the Convention reaffirmed the expectation of chastity and fidelity in relationships.

- In 1991 the Convention restated that "physical sexual expression" is only appropriate within a monogamous "union of husband and wife". The Convention also called on the church to "continue to reconcile the discontinuity between this teaching and the experience of members", referring both to dioceses that have chosen to bless monogamous same-sex unions and to general tolerance of premarital relations.[48]

- In 2000 the Convention affirmed "the variety of human relationships in and outside of marriage" and acknowledged "disagreement over the Church's traditional teaching on human sexuality."[120]

- The 2006 General Convention affirmed "support of gay and lesbian persons and children of God"; calls on legislatures to provide protections such as bereavement and family leave policies; and opposes any state or federal constitutional amendment that prohibits same-sex civil marriages or civil unions."[121]

- The 2009 General Convention affirmed that "gays and lesbians (that are) in lifelong committed relationships," should be ordained, saying that "God has called and may call such individuals to any ordained ministry in the Episcopal Church."[122] The Convention also voted to allow bishops to decide whether or not to bless same-sex marriages.[123]

On slavery

In 1861 a pamphlet titled A Scriptural, Ecclesiastical, and Historical View of Slavery written by John Henry Hopkins attempted to justify slavery based on the New Testament and gave a clear insight into the Episcopal Church's involvement in slavery. "Bishop Hopkins Letter on Slavery Ripped Up and his Misuse of the Sacred Scriptures Exposed" written by an anonymous Clergyman in 1863 opposed the points mentioned in Hopkin's pamphlet and revealed a startling divide in the Episcopal Church over the issue of slavery.

Charitable works

Episcopal Relief and Development

Episcopal Relief and Development is the international relief and development agency of the Episcopal Church of the United States. It helps to rebuild after disasters and aims to empower people by offering lasting solutions that fight poverty, hunger and disease. Episcopal Relief and Development programs focus on alleviating hunger, improving food supply, creating economic opportunities, strengthening communities, promoting health, fighting disease, responding to disasters, and rebuilding communities.[124]

Scholarships

There are about 60 trust funds administered by the Episcopal church which offer scholarships to young people affiliated with the church. Qualifying considerations often relate to historical missionary work of the church among American Indians and African-Americans, as well as work in China and other foreign missions.[125][126] There are special programs for both American Indians[127] and African-Americans[128] interested in training for the ministry.

Ecumenical relations

Like the other churches of the Anglican Communion, the Episcopal Church has entered into full communion with the Old Catholic Churches of the Union of Utrecht, the Philippine Independent Church, and the Mar Thoma Syrian Church of Malabar. The Episcopal Church is also in a relationship of full communion with the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America[129] and the Northern Province of the Moravian Church in America.

The Episcopal Church itself maintains ecumenical dialogs with the United Methodist Church, the Roman Catholic Church, and the Moravian Church in America, and participates in pan-Anglican dialogs with the Oriental Orthodox Churches, the World Alliance of Reformed Churches, and the Roman Catholic Church. In 2006 a relation of interim Eucharistic sharing was inaugurated with the United Methodist Church, a step that may ultimately lead to full communion.

Historically Anglican churches have had strong ecumenical ties with the Eastern Orthodox Churches, and the Episcopal Church particularly with the Russian Orthodox Church, but relations in more recent years have been strained, following the ordination of women and the ordination of Gene Robinson to the episcopate. A former relation of full communion with the Polish National Catholic Church (itself once a part of the Union of Utrecht) was broken off by the PNCC in 1976 over the ordination of women.

The Episcopal Church was a founding member of the Consultation on Church Union and participates in its successor, Churches Uniting in Christ. The Episcopal Church is a founding member of the National Council of Churches, the World Council of Churches, and the new Christian Churches Together in the USA. Dioceses and parishes are frequently members of local ecumenical councils as well.

See also

- Complete list of Presiding Bishops

- Dioceses of the Episcopal Church in the United States of America

- Succession of Bishops of the Episcopal Church in the United States

- List of colleges and seminaries affiliated with the Episcopal Church

- Churches Uniting in Christ

- Anglican realignment

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 NCC 2010 Yearbook

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 edited by F. L. Cross.; F. L. Cross (Editor), E. A. Livingstone (Editor) (13 March 1997). The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, 3rd edition. USA: Oxford University Press. p. 554. ISBN 0-19-211655-X.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Episcopal Church". The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. Columbia University Press. 2001-05. http://www.bartleby.com/65/ep/Episcopal.html. Retrieved 2007-09-09.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Episcopal Church USA". Encyclopedia Britannica. Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc.. http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9061604/Episcopal-Church-USA. Retrieved 2007-09-09.

- ↑ National Council of Churches News Service. "Catholics, Mormons, Assemblies of God growing; Mainline churches report a continuing decline". February 12, 2010. Accessed June 22, 2010.

- ↑ "What makes us Anglican? Hallmarks of the Episcopal Church". Episcopalchurch.org. http://www.episcopalchurch.org/visitors_8950_ENG_HTM.htm. Retrieved 2008-11-16.

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 7.11 7.12 7.13 7.14 7.15 7.16 7.17 7.18 7.19 7.20 7.21 7.22 7.23 7.24 7.25 7.26 7.27 7.28 7.29 7.30 Hein, David; Gardiner H. Shattuck, Jr. (2004). The Episcopalians. New York: Church Publishing. ISBN 0898694973.

- ↑ Episcopal Ministry: The Report of the Archbishops' Group.... Church House Publishing. 1990. p. 123. ISBN 0715137360.

- ↑ Goodstein, Laurie. Episcopal Bishops Give Ground on Gay Marriage. The New York Times. 15 July 2009.

- ↑ 1979 General Convention resolution to change the Oath of Conformity.

- ↑ 1985 General Convention resolution to rename the church.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 "Constitution & canons (2006) Together with the Rules of Order for the government of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America otherwise Known as The Episcopal Church" (PDF). The General Convention of The Episcopal Church. 2006. http://www.episcopalarchives.org/e-archives/canons/CandC_FINAL_11.29.2006.pdf. Retrieved 7 September 2007.

- ↑ Zahl, Paul F. (1998). The Protestant Face of Anglicanism. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publish Company. ISBN 0802845975.. The author is the former dean of Cathedral Church of the Advent, Birmingham, Alabama and the Trinity Episcopal School for Ministry. Quotes: "Protestant consciousness within ECUSA, which used to be called PECUSA (i.e., the Protestant Episcopal Church in the U.S.A) is moribund" (p. 56); "With the approval and lightening ascent of the 1979 Prayer Book came to the end, for all practical purposes, of Protestant churchmanship in what is now known aggressively as ECUSA" (p. 69).

- ↑ An example of an official Episcopal Church document in English, Spanish and French Retrieved 29 August 2007.

- ↑ [1] 2003 Constitution in Spanish] Retrieved 1 September 2007

- ↑ "Episcopal Church webpage in Spanish". Episcopalchurch.org. http://www.episcopalchurch.org/index_esn.htm. Retrieved 2008-11-16.

- ↑ "Episcopal Church webpage in French". Episcopalchurch.org. http://www.episcopalchurch.org/index_fra.htm. Retrieved 2008-11-16.

- ↑ Provincial Directory on the Anglican Communion Official Website

- ↑ "Anglicans Online|The online centre of the Anglican / Episcopal world". Morgue.anglicansonline.org. http://morgue.anglicansonline.org/061029/. Retrieved 2008-11-16.

- ↑ The Episcopal Church Retrieved 7 July 2007

- ↑ Sydnor, William (1980). Looking at the Episcopal Church. USA: Morehouse Publishing. p. 64.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Sydnor, William (1980). Looking at the Episcopal Church. USA: Morehouse Publishing. p. 72.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Carrington, Philip (1963). The Anglican Church in Canada. Toronto: Collins.

- ↑ Olmstead, Clifton E. (1960). History of Religion in the United States. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall. p. 45.

- ↑ James B. Bell. A War of Religion: Dissenters, Anglicans, and the American Revolution (2008)

- ↑ McConnell 2003

- ↑ Bonomi 1998, 201

- ↑ Jennifer. Clark, "'Church of Our Fathers': The Development of the Protestant Episcopal Church within the Changing Post-Revolutionary Anglo-American Relationship," Journal of Religious History, Feb 1994, Vol. 18 Issue 1, pp 27-51

- ↑ Thomas E. Buckley, "Evangelicals Triumphant: The Baptists' Assault on the Virginia Glebes, 1786-1801," William and Mary Quarterly, Jan 1988, Vol. 45 Issue 1, pp 33-70 in JSTOR

- ↑ Piepkorn, Arthur Carl (1977). Profiles in Belief: The Religious Bodies of the United States and Canada. Harper & Row. p. 199. ISBN 0060665807.

- ↑ Robert Bruce Mullin, "The Office of Bishop among Episcopalians, 1780-1835," Lutheran Quarterly, Spring 1992, Vol. 6 Issue 1, pp 69-83

- ↑ "UBE History". Ube.org. http://www.ube.org/history.html. Retrieved 2008-11-16.

- ↑ "UBE History". Episcopalchurch.org. http://www.episcopalchurch.org/5888_58502_ENG_HTM.htm. Retrieved 2008-11-16.

- ↑ Lockert B. Mason, "Separation and Reunion of the Episcopal Church, 1860-1865: The Role of Bishop Thomas Atkinson," Anglican and Episcopal History, Sept 1990, Vol. 59 Issue 3, pp 345-365

- ↑ Diana Hochstedt Butler, Standing against the Whirlwind: Evangelical Episcopalians in Nineteenth-Century America (1995)

- ↑ Peter W. Williams, "The Gospel of Wealth and the Gospel of Art: Episcopalians and Cultural Philanthropy from the Gilded Age to the Depression," Anglican and Episcopal History, Jun 2006, Vol. 75 Issue 2, pp 170-223

- ↑ "Episcopal Shield". Kingofpeace.org. http://www.kingofpeace.org/shield.htm. Retrieved 2008-11-16.

- ↑ http://www.episcopalchurch.org/75383_73867_ENG_HTM.htm

- ↑ Frum, David (2000). How We Got Here: The '70s. New York, New York: Basic Books. p. 17. ISBN 0465041957.

- ↑ The Archbishop of Canterbury's Presidential Address, paragraph 5.

- ↑ The Archives of the Episcopal Church, Acts of Convention: Resolution #1991 B051, Call for the Removal of Racism from the Life of the Nation. Retrieved 2008-10-31.

- ↑ Bishops Endorse Apology for Slavery Complicity

- ↑ The Philadelphia Eleven, and the consecrating bishops, are listed in the Philadelphia 11 article on The Episcopal Church website (retrieved November 5, 2006).

- ↑ The Archives of the Episcopal Church, Acts of Convention: Resolution #1976-B300, Express Mind of the House of Bishops on Irregularly Ordained Women. Retrieved 2008-10-31.

- ↑ Bishop Harris is also the first African-American woman bishop. Office of Black Ministries, The Episcopal Church

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 The Archives of the Episcopal Church, Acts of Convention: Resolution #1997-A053, Implement Mandatory Rights of Women Clergy under Canon Law. Retrieved 2008-10-31.

- ↑ "Episcopal Diocese of Quincy seeks alternative oversight". Episcopalchurch.org. http://www.episcopalchurch.org/3577_77919_ENG_HTM.htm. Retrieved 2008-11-16.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 The Archives of the Episcopal Church, Acts of Convention: Resolution #1991-A104, Affirm the Church's Teaching on Sexual Expression, Commission Congregational Dialogue, and Direct Bishops to Prepare a Pastoral Teaching. Retrieved 2008-10-31.

- ↑ 76th General Convention Legislation, Resolution C056. Accessed August 18, 2010.

- ↑ The Archives of the Episcopal Church, Acts of Convention: Resolution #2003-C004, Oppose Certain Therapies for Sexual Orientation. 2008-10-31.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Laurie Goodstein,Episcopal Vote Reopens a Door to Gay Bishops, The New York Times, July 14, 2009. Retrieved on July 21, 2009.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Goodstein, Laurie (2009-07-15). "Episcopal Vote Reopens a Door to Gay Bishops". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2009/07/15/us/15episcopal.html. Retrieved 2010-05-02.

- ↑ Tom Wright,The Americans know this will end in schism—Support by US Episcopalians for homosexual clergy is contrary to Anglican faith and tradition. They are leaving the family, The Times, July 15, 2009. Retrieved on July 21, 2009.

- ↑ Resolution D025

- ↑ "''A Bishop Speaks: Homosexual History'' by John Shelby Spong, retrieved November 4, 2006". Beliefnet.com. http://www.beliefnet.com/story/130/story_13022_3.html. Retrieved 2008-11-16.

- ↑ "The Episcopal Church And Homosexuality: Activities during 1996". Religioustolerance.org. http://www.religioustolerance.org/hom_epis2.htm. Retrieved 2008-11-16.

- ↑ Anglicans Online: The Trial of Bishop Walter Righter.

- ↑ Adams, Elizabeth (2006). Going to Heaven: The Life and Election of Bishop Gene Robinson. Brooklyn, NY: Soft Skull Press. ISBN 1933368225.

- ↑ Anglican Communion News Service

- ↑ "The 2004 Windsor Report Appendices". Anglicancommunion.org. http://www.anglicancommunion.org/windsor2004/appendix/p3.6.cfm. Retrieved 2008-11-16.

- ↑ Theologians offer response to Windsor Report request: Paper cites 40-year consideration of same-gender relationships from Episcopal News Service.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 62.2 "Rick Warren to address breakaway Anglicans". http://www.christiantoday.com/article/rick.warren.to.address.breakaway.anglicans/23149.htm.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 "Pastor Rick Warren, Metropolitan Jonah, the Rev. Dr. Todd Hunter to Address ACNA Assembly". http://www.united-anglicans.org/stream/2009/04/assemblyspeakers.html.

- ↑ "News & Announcements". Anglicancatholic.org. http://www.anglicancatholic.org/affirmstlouis.html. Retrieved 2008-11-16.

- ↑ Goodstein, Laurie; Marshall, Carolyn (2006-12-03). "Episcopal Diocese Votes to Secede From Church". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2006/12/03/us/03episcopal.html?ex=1322802000&en=2b7ab526f61329c4&ei=5088&partner=rssnyt&emc=rss. Retrieved 2010-05-02.

- ↑ Role of gays prompts split in Episcopal Church, AP/CNN, December 8, 2007

- ↑ "Episcopal Diocese Votes to Secede From Church", an article in The New York Times by Laurie Goodstein and Carolyn Marshall, December 3, 2006

- ↑ http://s3.amazonaws.com/dfc_attachments/public/documents/356/Order-MSA.PDF

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 69.2 Joe Mandak, Associated Press (2008-10-06). "Pittsburgh diocese votes to split from Episcopal Church - USATODAY.com". Usatoday.com. http://www.usatoday.com/news/religion/2008-10-06-episcopal-divided_N.htm. Retrieved 2008-11-16.

- ↑ Terry Lee Goodrich (November 15, 2008). "Fort Worth Episcopal Diocese votes to leave mother church". Fort Worth Star-Telegram. http://www.star-telegram.com/804/story/1041377.html.

- ↑ S.G. Gwynne (1 February 2010). "Bishop takes Castle". Texas Monthly. http://www.texasmonthly.com/2010-02-01/letterfromfortworth-1.php. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ↑ In re: Franklin Salazar et. al., [2] (2nd Court of Appeals, Fort Worth 16 November 2009).

- ↑ Oral argument In re: Salazar et al. Second Court of Appeals, Fort Worth. 27 April 2010. http://www.2ndcoa.courts.state.tx.us/oa/2009/09405CV.mp3. Retrieved 2 May 2010

- ↑ Rector, Wardens v. Episcopal Church 620 A.2d 1280, 1293 (Conn. 1993) The court stated the local church “had agreed, as a condition to their formation as ecclesiastical organizations affiliated with the Diocese and [the Episcopal Church], to use and hold their property only for the greater purposes of the church.” (Id. at p. 1292.) Specifically an Episcopal Church law, (which it called the “Dennis Canon”), “adopted in 1979 merely codified in explicit terms a trust relationship that has been implicit in the relationship between local parishes and dioceses since the founding of [the Episcopal Church] in 1789.” (Ibid.) Accordingly, it found “a legally enforceable trust in favor of the general church in the property claimed by the [local church].”

- ↑ http://www.virtueonline.org/portal/modules/news/article.php?storyid=9599

- ↑ "Press release by the Diocese of Virginia". Thediocese.net. http://www.thediocese.net/News_services/pressroom/newsrelease25.html. Retrieved 2008-11-16.

- ↑ "Judge Schwartz Order on Grace Church". Public Record. http://www.graceandststephens.org/news/Judge%20Schwartz%27s%20Order%20on%20Grace%20Church%20032409.pdf. Retrieved 2009-03-26.; see also, http://www.courtinfo.ca.gov/opinions/revpub/D051120.PDF

- ↑ In re Episcopal Church Cases, Case No. S155094 This decision took numerous arguments into account, including court rulings on similar Episcopal Church cases in other states: "Other Episcopal Church cases reaching similar conclusions include: Bishop and Diocese of Colorado v. Mote (Colo. 1986) 716 P.2d 85; Episcopal Diocese of Mass. v. Devine (Mass.App.Ct. 2003) 797 N.E.2d 916 (relying on Canon I.7.4 and the fact the local church had agreed to accede to the general church’s canons); Bennison v. Sharp (Mich.Ct.App. 1983) 329 N.W.2d 466; Protestant Episc. Church, etc. v. Graves (N.J. 1980) 417 A.2d 19; The Diocese v. Trinity Epis. Church (App.Div. 1999) 684 N.Y.S.2d 76, 81 (“[T]he ‘Dennis Canon’ amendment expressly codifies a trust relationship which has implicitly existed between the local parishes and their dioceses throughout the history of the Protestant Episcopal Church,” citing Rector, Wardens v. Episcopal Church, supra, 620 A.2d 1280); Daniel v. Wray (N.C.Ct.App. 2003) 580 S.E.2d 711 (relying on Canon I.7.4); In re Church of St. James the Less (Pa. 2005) 888 A.2d 795 (relying on Canon I.7.4 and citing Rector, Wardens v. Episcopal Church, supra, 620 A.2d 1280)."

- ↑ [http://www.ncccusa.org/news/100204yearbook2010.html "Catholics, Mormons, Assemblies of God growing; Mainline churches report a continuing decline"]. National Council of Churches USA. 2010-02-12. http://www.ncccusa.org/news/100204yearbook2010.html. Retrieved 2010-02-21.

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 From 2007 Parochial Reports. Source: The General Convention Office as of January 2009 Retrieved June 16, 2009

- ↑ "Mainline Protestant churches no longer dominate". Episcopalchurch.org. http://www.episcopalchurch.org/3577_60792_ENG_HTM.htm. Retrieved 2008-11-16.

- ↑ Is the Episcopal Church Growing (or Declining)? by C. Kirk Hadaway Director of Research, The Episcopal Church Center, Retrieved 2007-10-25

- ↑ Q&A Context, analysis on Church membership statistics, Retrieved 2007-10-25

- ↑ Episcopal Fast Facts: 2005, Retrieved 2007-10-25

- ↑ Overview of Membership, Attendance and Giving Trends in the Episcopal Church, Retrieved 2007-10-25

- ↑ "Episcopal membership loss 'precipitous'", The Christian Century, November 14, 2006, Retrieved 2007-10-27

- ↑ 87.0 87.1 [3] Data from the National Council of Churches' Historic Archive CD and Yearbook of American and Canadian Churches

- ↑ [4] Data from the 2000 Religious Congregations and Membership Study

- ↑ "The Anglican Communion Official Website: Iglesia Episcopal de Cuba". Anglicancommunion.org. http://www.anglicancommunion.org/tour/province.cfm?ID=Y2. Retrieved 2008-11-16.

- ↑ Church Governance.

- ↑ "What's Happening at 815?". Episcopalchurch.org. http://www.episcopalchurch.org/lw_whatshappening.htm. Retrieved 2008-11-16.

- ↑ The Archives of the the Episcopal Church, Acts of Convention: Resolution #2000-B034, Apologize to Those Offended During Liturgical Transition to the 1979 Book of Common Prayer. Retrieved 2008-10-31.

- ↑ A Basic Introduction to Christianity from the Visitor's section of the Episcopal website.

- ↑ Joseph Buchanan Bernardin, An Introduction to the Episcopal Church (2008) p. 63

- ↑ "Visitors' Center". Episcopalchurch.org. http://www.episcopalchurch.org/visitors_10898_ENG_HTM.htm. Retrieved 2008-11-16.

- ↑ Authority, Sources of (in Anglicanism) on the Episcopal Church site, accessed on April 19, 2007, which in turn credits Church Publishing Incorporated, New York, NY, from An Episcopal Dictionary of the Church, A User Friendly Reference for Episcopalians, Don S. Armentrout and Robert Boak Slocum, editors.

- ↑ Anglican Listening on the Episcopal Church site goes into detail on how scripture, tradition, and reason work to "uphold and critique each other in a dynamic way".